by Eric Howes (Principal Lab Researcher) & Ryann Falke (Sales Development Representative)

Last week we documented several interesting credentials phishes delivered through LinkedIn itself. Although these Wells Fargo phishes were identically worded, they were delivered to two different victims in two different ways.

In the first, a victim received a Wells Fargo phish from a fake Wells Fargo LinkedIn profile in his LinkedIn Messages. In the second, a potential mark received the same phish from the same fake LinkedIn profile but delivered to the external email address associated with his LinkedIn profile (and not visible to other users on LinkedIn).

It was second phish that got our attention, as it was clear that malicious actors had figured out how to use LinkedIn to deliver malicious emails through LinkedIn itself to email inboxes outside of LinkedIn. In short, they had converted LinkedIn itself into a phishing platform.

Not being overly familiar with LinkedIn's messaging functionality, we endeavored to figure out how they did it. After a few days of research and testing, we think we have (most of) the answer.

Questions & Assumptions

Following our initial blog post, we had a number of questions. What type of account or profile on LinkedIn did the bad guys use? Did they need to establish a reputation for that bogus Wells Fargo account by soliciting connections from real users ahead of time? What precise steps did they take to generate that custom phishing email to an external email address? What monetary costs, if any, would be associated with this kind of attack? How well or how easily would this kind of attack scale?

We were assuming that the bad guys had been using a Premium business account of some sort that would give them special functionality within LinkedIn not available to regular individual user accounts -- even Premium individual accounts. We were also assuming that these malicious actors had tricked their marks into accepting Connection Requests from the fake Wells Fargo account they had set up.

In fact, the process that we worked out turned out to be much simpler (and cheaper) than that. So far as we can tell, the bad guys probably used a process along these lines.

How They (Likely) Did It

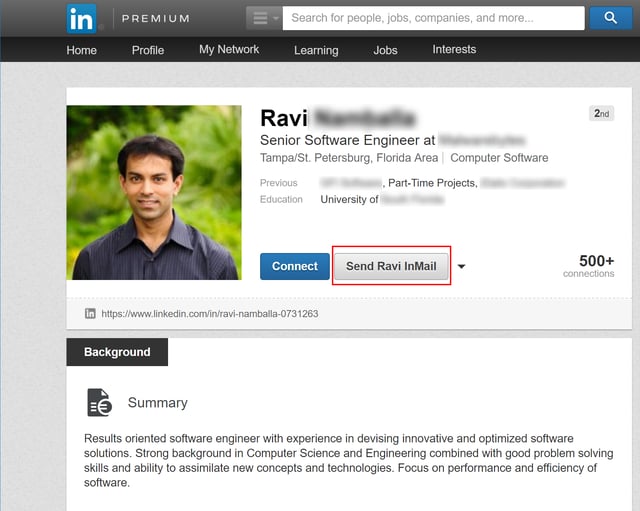

First, the bad guys would have created a dummy email account to supply the basis for a fake identity used to create a bogus Premium LinkedIn profile. That bogus LinkedIn profile was probably an individual account (as opposed to a business account) and used the name of a person and not a company. An individually named account would be more likely to generate accepted Connection Requests from other individual LinkedIn users, who are more likely to respond to a Request from a personal account rather than a business account. More importantly, however, if the bad guys had made the initial LinkedIn profile with the Wells Fargo name, it would have attracted attention from Wells Fargo itself as well as LinkedIn. However it was named, the LinkedIn account may well have been a free individual account that was later upgraded (for free) to a Premium account to allow the bad guys to send InMails.

Second, after creating the dummy account, the bad guys likely built trust or reputation for that profile by sending Connection Requests to actual LinkedIn users -- possibly even Wells Fargo employees (more on which shortly). Although we cannot be sure how many users accepted those bogus Connection Requests, we assume a significant number did accept the invitations, based on previous reports of malicious actors successfully building apparently reputable fake LinkedIn profiles. Unfortunately, LinkedIn shut down this bogus profile or account before we could examine it, so information about it remains extremely limited.

Third, while building that fake profile's reputation, the bad guys must have also been using LinkedIn to reconnoiter and identify potential marks. This attack gives the appearance of being a highly targeted attack against a small number of users who had likely been identified as potential Wells Fargo customers. We are speculating that the bad guys used LinkedIn to identify potential Wells Fargo customers by looking for connections between LinkedIn users and the official Wells Fargo's LinkedIn Business account or to Wells Fargo employees. Connections between the bad guys' fake profile and Wells Fargo employees or the main Wells Fargo profile would have aided this endeavor. That said, we still do not fully understand the precise methodology of how they exploited LinkedIn to identify potential marks.

Fourth, after generating sufficient connections to build the reputation of their fake LinkedIn profile, the bad guys probably changed the name on the account from that of a fictitious person to the name of Wells Fargo itself -- probably shortly before they launched the attack. They likely also upgraded their free individual account to a Premium account at this time, allowing them to send InMail.

Truth be told, the malicious actors may not have even needed to build the fake profile's reputation, as the social engineering in this phish relied not on the account's reputation within LinkedIn, but the reputation of the company name and brand with potential marks.

How We Tested

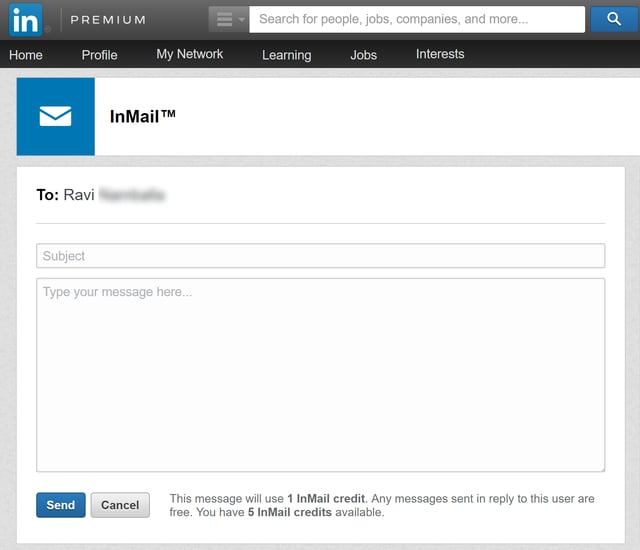

InMail was critical to this attack, as it allowed the bad guys to generate custom messages delivered to external email addresses associated with their marks' LinkedIn profiles, even when those email addresses were unknown to the attackers. And the fact that the generated emails were delivered through LinkedIn's own servers virtually guaranteed that they would sail through most email security solutions.

So, we went looking for a cheap and easy way to generate InMails. The solution turned out to be much simpler and cheaper than we thought.

First, we upgraded one of our own personal free accounts to a basic Premium account. Although this upgrade process involved supplying credit card information, that would have presented little problem to malicious actors with ready access to the booming online black market in compromised credit cards. Upon upgrading, LinkedIn gave us a 30-day free trial of the Premium account. Included in this free trial were five InMail credits, which allowed us to send InMail to users with whom we were not yet connected.

InMail credits can be purchased through a Premium LinkedIn account. Each InMail credit costs $10, but when you sign up for a Premium account, the user gets 5 free InMail credits. Users receive credit back once recipients respond. LinkedIn Premium account holders can accumulate InMail credits from month to month, but they will expire after 90 days. Users in need of additional InMail credits can purchase up to 10 more InMail credits than allowed by the account type or upgrade the account for even more.

We tested our Premium account capabilities by sending InMails to users we know but with whom we were not yet connected with on LinkedIn.

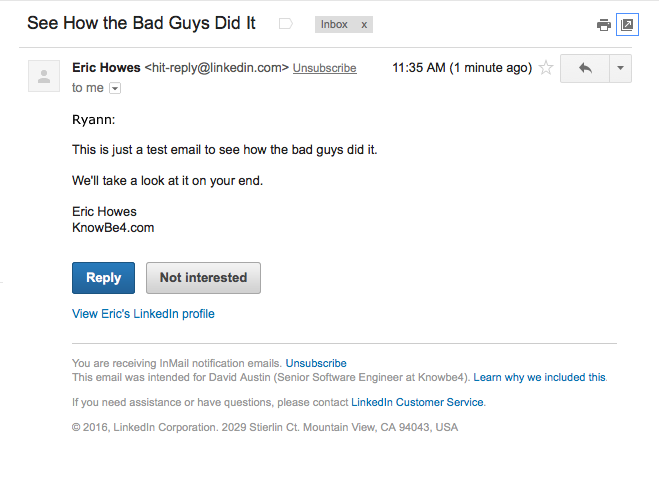

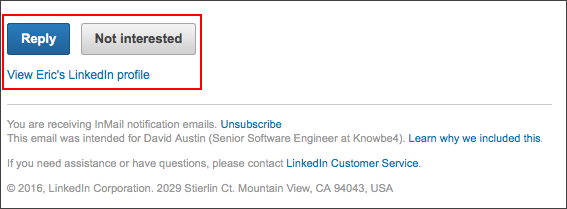

We then monitored and checked the InMails that arrived at these users external email accounts. The InMails delivered to these external accounts were a close match for the actual Wells Fargo phish that the second victim received.

First, there was no boiler plate, and the InMail message was completely customized, unlike standard LinkedIn messages such as Connection Requests, etc.

Second, the footer links in our test InMail's were of the same format and type as the victim's Wells Fargo phish.

Third, key LinkedIn-specific headers were almost identical.

Received: from mailb-ac.linkedin.com (mailb-ac.linkedin.com. [108.174.3.147])

by mx.google.com with ESMTPS id a79si20335515qka.32.2016.11.08.08.35.52

for <REDACTED>

(version=TLS1_2 cipher=ECDHE-RSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256 bits=128/128);

Tue, 08 Nov 2016 08:35:52 -0800 (PST)

X-LinkedIn-Class: INMAIL

X-LinkedIn-Template: inmail_sent

X-LinkedIn-fbl: m2-aszy55jq6jjai71tfqlgane6427k8ywj9g18u09ptalle0xuti2xztv3sfl3mv9zb5mjrind8nvdihlwvh9z2tn0rxjbreo3rwq4iv

X-LinkedIn-Id: 1yk79s-iv9pxdcq-v3

List-Unsubscribe: <https://www.linkedin.com/e/v2?e=1yk79s-iv9pxdcq-v3&t=lun&midToken=AQGy5rmPsM8ppg&ek=inmail_sent&loid=AQGDAkjWzJvw6gAAAVhEy7gh9ySdUH6Uh61_6dVGt-EQ6QXfFZReOBM0APfen63FOcWVm79lINMgPlg&eid=1yk79s-iv9pxdcq-v3>

If the bad guys didn't use this very same process for generating InMails to the email accounts of customers outside of LinkedIn, they must have used something very close to it.

What We Learned

Again, the entire process for generating custom LinkedIn InMails to external email addresses was much easier than we had anticipated. That said, one key question remains: how well would this type of attack scale?

In fact, we doubt this kind of attack would scale very well. InMail is sent on an individual basis and, as far as we know, cannot be sent en masse or in any kind of automated fashion. Moreover, although one can get free InMail credits from LinkedIn by simply signing up for a Premium account, individual InMails are somewhat costly, as noted above. Finally, anyone who wanted to exploit this attack vector over an extended period of time would need to incur the full expense of a Premium account. And even then, any account used for an attack would be at risk for being shut down by LinkedIn itself (as happened in the case we documented).

This particular attack vector would, however, be potentially very useful for low volume, specially crafted spear-phishing attacks against high value targets. LinkedIn is a very attractive platform for identifying potential marks, building trusted profiles for use in social engineering schemes, and delivering emails to external addresses while piggybacking on the reputation of LinkedIn's own email servers to skirt a wide variety of email security solutions.

Malicious parties might well find the process we used -- a free individual LinkedIn account upgraded to a Premium status -- entirely satisfactory for a series of low volume campaigns. Although somewhat labor intensive, the costs of exploiting this attack vector would otherwise be negligible and the unique advantages significant enough to justify its use.

The Wells Fargo phish we documented last week was most likely part of a test campaign -- a "proof of concept" exercise designed to explore the potential utility of LinkedIn for social engineering and phishing. This kind of basic credentials phish is probably not well suited for such an exotic attack vector (most Wells Fargo customers would probably not be anticipating account notices from Wells Fargo to be delivered through InMail). This attack vector could be adapted to other more specialized types of social engineering attacks, however, which we anticipate exploring in future blog posts.

End users need to be trained to recognize these types of targeted attacks. Old-school awareness training simply does not cut it anymore. Users need to be stepped through new-school security awareness training which provides on-demand interactive modules combined with frequent simulated phishing attacks. Start your awareness program with a free one-time simulated Phishing Security Test.

Don't like to click on redirected buttons? Copy and pastethis link into your browser:

https://www.knowbe4.com/phishing-security-test-offer