A lengthy and fascinating article in the New York Times by Andrew E. Kramer and Andrew Higgens on August 16, 2017 reported that a Ukranian coder known to his friends on the “dark web” as “Profexer” vanished last winter after leaving his friends some final notes in his private restricted- access web site before voluntarily given himself up to the Ukrainian authorities.

A code snippet shows he may be indirectly linked to the DNC election hacking incident that resulted in a cache of 19,252 internal emails and 8,034 attachments from the DNC, making its way to WikiLeaks and published on July 22, 2016 which is under investigation. The authorities had been perplexed as to why a Russian hack used Ukrainian players.

On December 29, 2016, the US Department of Homeland Security, in a NCCIC Joint Analysis Report (JAR) released technical evidence suggesting that “Russian civilian and military intelligence Services (RIS) compromise and exploited networks and endpoints associated with the U.S. election, as well as a range of U.S. Government, political, and private sector entities.

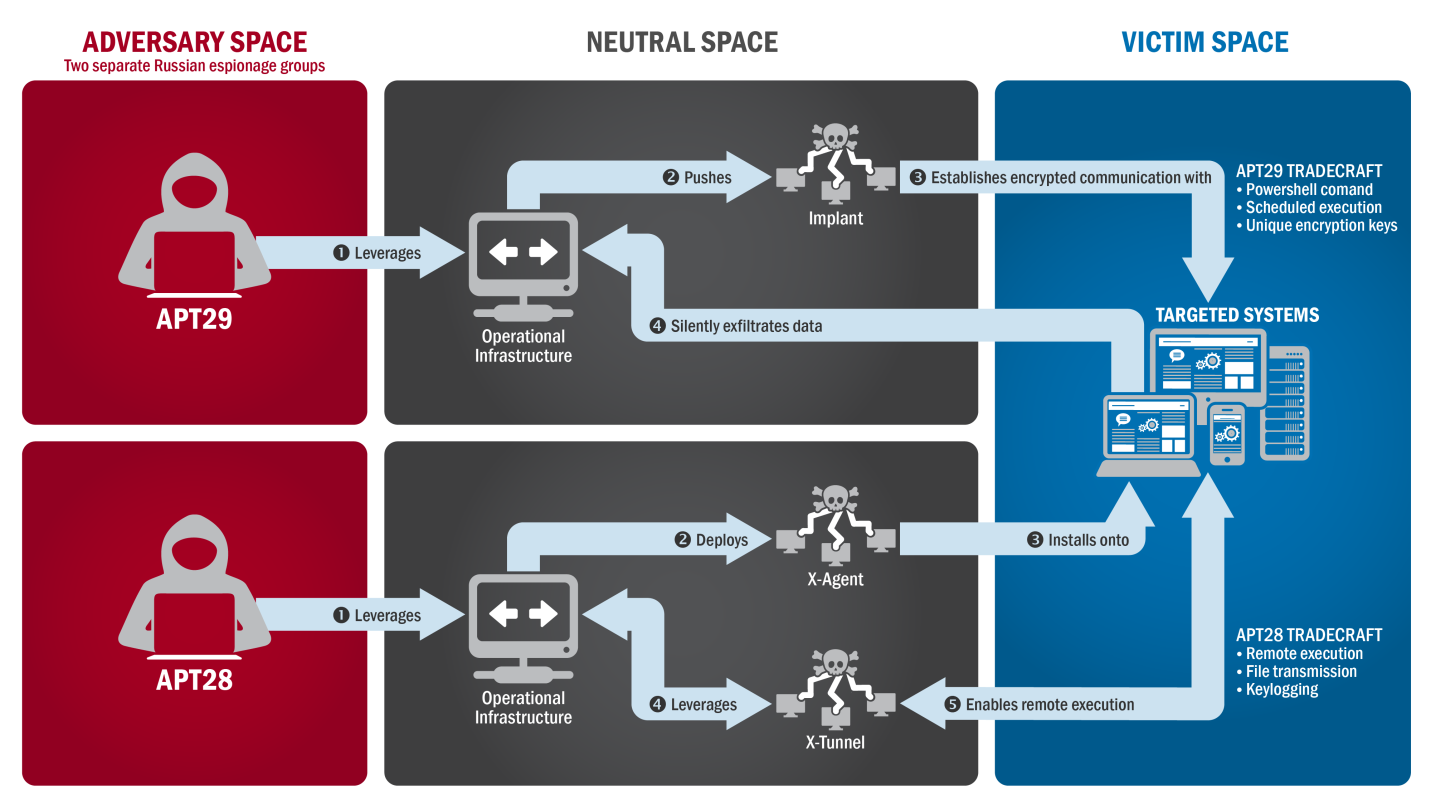

The tools of the trade cited were one malware component and tactics including spear phishing of a campaign directed to targets using (RATs) or Remote Acess Tools. According to the JAR, there were two Russian group involved. “The first actor group, known as Advanced Persistent Threat APT 29, entered into the party’s systems in summer 2015, while the second, known as APT28, entered in spring 2016”.

Both APT28 and APT 29 have slightly different specialities that were involved in both attacks and each used them effectively in both attacks. Here’s how the Joint Analysis Report described GRIZZLY STEPPE – Russian Malicious Cyber ActivitySummary

“Both groups have historically targeted government organizations, think tanks, universities, and corporations around the world. APT29 has been observed crafting targeted spearphishing campaigns leveraging web links to a malicious dropper; once executed, the code delivers Remote Access Tools (RATs) and evades detection using a range of techniques. APT28 is known for leveraging domains that closely mimic those of targeted organizations and tricking potential victims into entering legitimate credentials.

APT28 actors relied heavily on shortened URLs in their spearphishing email campaigns. Once APT28 and APT29 have access to victims, both groups exfiltrate and analyze information to gain intelligence value. These groups use this information to craft highly targeted spearphishing campaigns. These actors set up operational infrastructure to obfuscate their source infrastructure, host domains and malware for targeting organizations, establish command and control nodes, and harvest credentials and other valuable information from their targets.

The first actor group, known as Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) 29, entered into the party’s systems in summer 2015.

Figure 1: The tactics and techniques used by APT29 and APT 28 to conduct cyber intrusions against target systems

While the second, known as APT28, entered in spring 2016:

Figure 2: APT28's Use of Spearphishing and Stolen Credentials

The only item known so far linking Profexer to the hack is a listing in the code trail of a malware toolkit Profexer sold on the dark web for donations of $3-$250 and is called The “PAS TOOL PHP WEB KIT.” The kit, allegedly written by Profexer and available on the dark web could have been bought by the Russians to include in larger set of tools which comprised the exploit.

This is the only known piece of evidence so far linking Profexer to the hack. It is widely thought by security experts that the Russian (RIS) is a distributed group of hackers under the direction of the two main groups APT28 and APT29.

Since Profexor sold his tools on the dark web in the Ukraine, the existing laws do not prohibit distribution and sale of malware kits from sites, only the actual use of them in a crime. So Profexer was not arrested. Whether he was further involved remains to be seen as the case moves forward. However, he may have felt it safer to participate as a witness then take his chances out in the wild.

The Ukranian police have said that he is now a witness for the FBI. Prior to turning himself in Profexor wrote in one of his last messages on his web site. According to the New York Times article his last messages were “It won’t be pleasant. But I’m still alive.”

[Updated: 8/18/2017]

After the New York Times story was published, several security researchers concluded that the story, although fascinating, was inaccurate. The New York Times story was based on a leap of faith from the “GRIZZLYSTEPPE” report that listed attack signatures commonly involved in Russian hacks. Brian Krebs from KrebsonSecurity noted:

“The Times’ reasoning for focusing on the travails of Mr. Profexer comes from the “GRIZZLYSTEPPE” report, a collection of technical indicators or attack “signatures” published in December 2016 by the U.S. government that companies can use to determine whether their networks may be compromised by a number of different Russian cybercrimegroups. The only trouble is nothing in the GRIZZLYSTEPPE report said which of those technical indicators were found in the DNC hack. In fact, Prefexer’s “P.A.S. Web shell” tool — a program designed to insert a digital backdoor that lets attackers control a hacked Web site remotely — was specifically not among the hacking tools found in the DNC break-in.

According to Crowdstrike, the company called in to examine the DNC’s servers following the intrusion. In a statement released to KrebsOnSecurity, Crowdstrike said it published the list of malware that it found was used in the DNC hack, and that the Web shell named in the New York Times story was not on that list.”

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2017/08/blowing-the-whistle-on-bad-attribution/

The New York Times also issued an official correction to the story.

Correction: August 16, 2017

An earlier version of this article misstated how a type of malware known as P.A.S. was used in Russian hacking efforts in the United States that included the electronic break-in at the Democratic National Committee. The agencies identified the malware as a tool used in Russian hacking, but they did not specify in which attacks it was used.

Phish Your Users With Office Document Attachments That Have Macros

It's a must these days to send all employees simulated phishing attacks with Office attachments that have macros and see if they open that document and click on "Enable Editing". If they do, that means a social engineering failure and they need to get some remedial training immediately. Also, give them access to the KnowBe4 free Phish Alert Button so that they can forward phishy emails to your Incident Response team.

We strongly recommend to phish your own users to prevent these types of very expensive snafus. If you're wondering how many people in your organization are susceptible to phishing, here is a free phishing security test (PST):