By Eric Howes, KnowBe4 Principal Lab Researcher.

For most users the experience of dealing with phishing emails is a solitary experience, whether they recognize that they are under attack or remain blissfully unaware of the dangers lurking behind seemingly innocuous emails hitting their inboxes. And therein lies a good part of the danger to organizations with employees susceptible to social engineering schemes. Left to their own devices, most employees are incapable of consistently identifying malicious emails for what they are and handling them properly. And the bad guys know this.

For most users the experience of dealing with phishing emails is a solitary experience, whether they recognize that they are under attack or remain blissfully unaware of the dangers lurking behind seemingly innocuous emails hitting their inboxes. And therein lies a good part of the danger to organizations with employees susceptible to social engineering schemes. Left to their own devices, most employees are incapable of consistently identifying malicious emails for what they are and handling them properly. And the bad guys know this.

Social engineering schemes are explicitly designed to exploit the innate trust that most users place in emails that appear to be routine and familiar. They are also crafted to capitalize on users' general ignorance of the threat landscape as well as the lengths to which malicious parties will go to trick unwitting employees into coughing up the keys to the kingdom.

Occasionally non-technically savvy employees do have an inkling that something seems "off" or "unusual" when confronted with malicious emails. For many the first instinct is to respond to the sender of a questionable email, asking for clarification, reassurance, and more information -- especially when they are being asked to click links or open attachments. This isn't an entirely bad course of action. At the very least such users are demonstrating some level of caution and awareness.

Over the past few months, however, we have noticed that malicious actors running mass phishing campaigns are increasingly prepared to respond to such hand-wringing inquiries from potential marks. Thus, users who ask for more information about questionable emails just might in fact get a response from the bad guys -- designed, of course, to appear as routine and innocuous as the original phishing email itself. The goal, of course, is to extend the social engineering scheme past the initial malicious email and into the kind of brief email exchange that denizens of the modern corporate workplace engage in every day.

In what follows we take a look at the kinds of responses that employees at your company or organization just might receive from malicious parties and point out some of the tell-tale signs that they might be dealing with a rat.

What Is...

Before we begin looking at the kinds of reassuring replies we've seen bad guys providing worried marks in recent phishing campaigns, let us review previous instances where malicious actors have been known to engage with the targets of their phishing missives. To be sure, it is not entirely unknown for the bad guys to get involved in a back and forth with potential marks, but such instances have typically been restricted to a few well-known types of phishing campaigns: wire fraud phishes and strikingly similar W-2 phishes, both of which see the bad guys spoofing CEOs and other senior executives within companies and organizations.

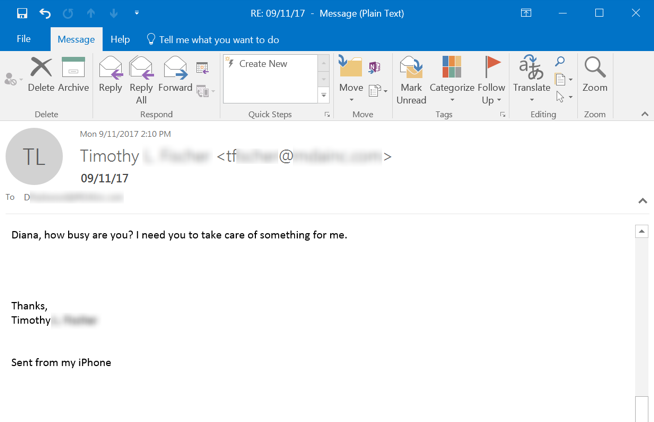

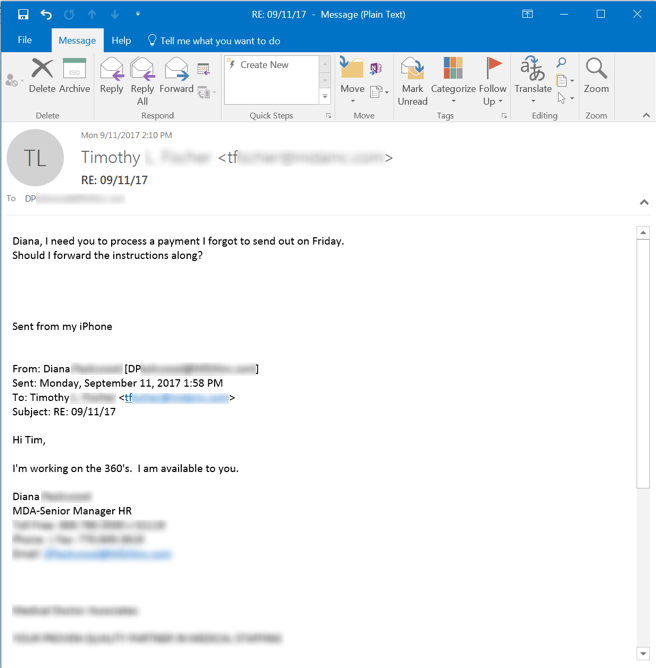

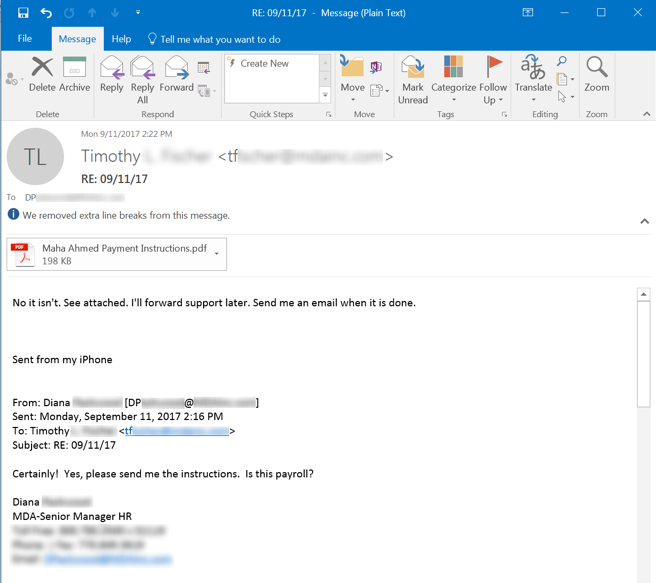

Here for, example, is a standard CEO fraud email in which a malicious actor spoofs the president of company with the intent of tricking an employee into wiring money to a bank account controlled by the bad guys. The initial salvo is both personal yet vague:

Clearly this is a social engineering scheme designed to solicit a response from the mark and kick off an email exchange. Notice also that the malicious actor assumes a role or persona who enjoys a specific, familiar, and well-defined relationship with the user, who responds:

Malicious groups who prosecute these kinds of phishing campaigns know going in that they will be required to adapt and roll with the punches, as no two marks can be guaranteed to respond to the initial email in exactly the same way. And, indeed, this particular employee throws a bit of a curve ball in her response, inquiring whether the requested wire transfer is payroll related -- a natural question given her position in HR.

Although the bad guy directly answers Diana's question and provides the information required to complete the wire transfer (in the form of an attached PDF), this particular exchange ends with the employee clicking the Phish Alert Button (PAB), effectively alerting her IT department to this suspected phishing attack.

Just why the bad guys chose a member of this organization's HR department is unknown. Perhaps Diana was the only employee who responded. Perhaps the bad guys preliminary research was flawed or incomplete. Whatever the case, this particular attempt to extract money from the targeted organization failed.

Nonetheless this is a fine example of the email exchanges we have seen the bad guys engaging in for a number of years when perpetrating BEC (business email compromise) or CEO fraud phishes. Initiated with the expectation of an email exchange, these targeted campaigns see the bad guys fluidly responding as normal employees would with the hopes of convincing the mark to give up the goods.

...and What Should Never Be

Over the past few months we have observed an increasing number of more "routine," non-targeted phishing campaigns being supported by bad guys are prepared to perform some amount of hand holding when potential marks express qualms about opening links and attachments offered to them as part of mass phishing campaigns.

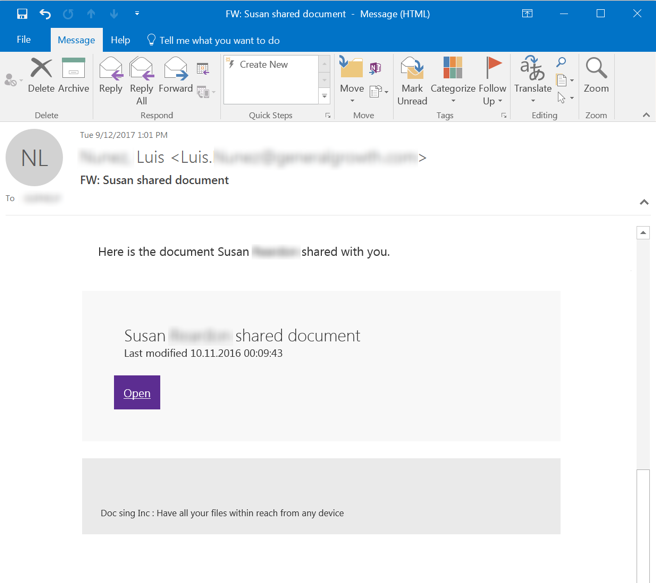

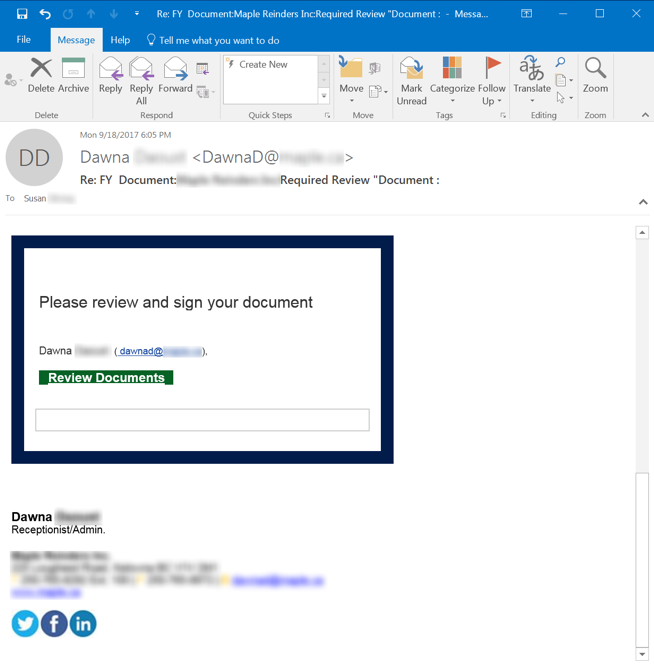

Here is a simple, straightforward example. This phish leads off with one of the more common social engineering lures currently in use: the fake document delivery or sharing scheme:

Note that this phish, which loosely spoofs the format used by a number of well-known online document delivery/sharing/signing services, claims to be offered to the user through a service called "Doc sing Inc."

The employee in this case senses something is amiss and hits the reply button, expressing reservations and seeking more information.

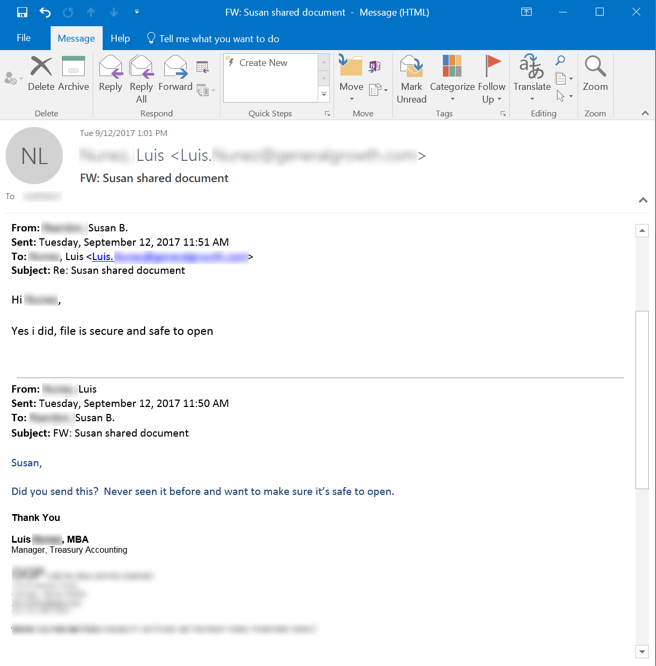

Sure enough, the malicious actor responds with assurances that the "file is secure and safe to open." But "Susan" makes a telling error in her response, addressing Luis by his last name instead of his first. Not surprisingly the user then hits the Phish Alert Button (PAB) in his instance of Outlook, again alerting IT staff to a phishing attack in progress on the company -- a wise move given that the embedded link led to a credentials phish.

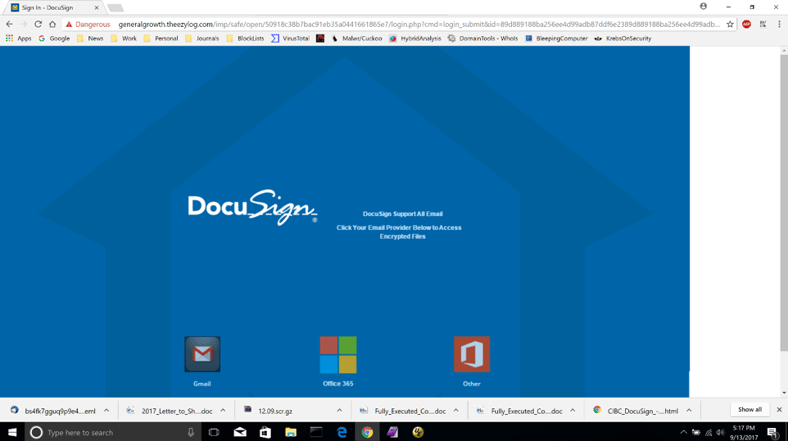

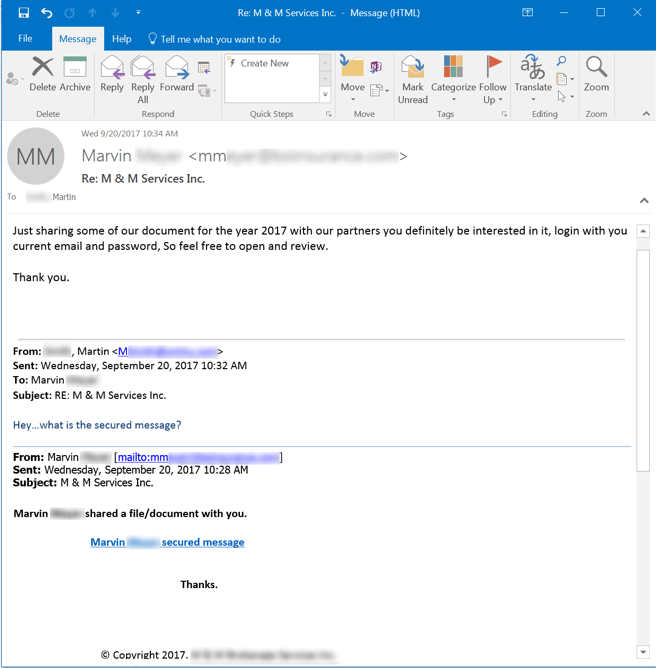

The bad guys' response in this example is fairly simple and straightforward, directly addressing the mark's expressed concerns about the safety of the link and file presented in the original email. But the bad guys who support these kinds of campaigns have demonstrated that they are capable of providing more context and information when potential marks demand it. Consider this brief exchange between "Marvin," the sender of yet another fake file sharing phish, and Martin, an employee who happened to receive this rather routine malicious email.

Notice that Martin has a fairly simple question about the purported file or message ("what is the secured message?"). The answer he receives, however, is fairly vague and gives the appearance of being boilerplate (complete with broken English). Once again, the employee in this situation hits the Phish Alert Button (PAB) to sound the alarm.

In our next example, the bad guys do manage to provide a more specific and complete explanation of the file being offered to the mark. Once again, the bad guys lead off with a routine file sharing phishing email:

And once again, the employee, Susan, responds with a simple question:

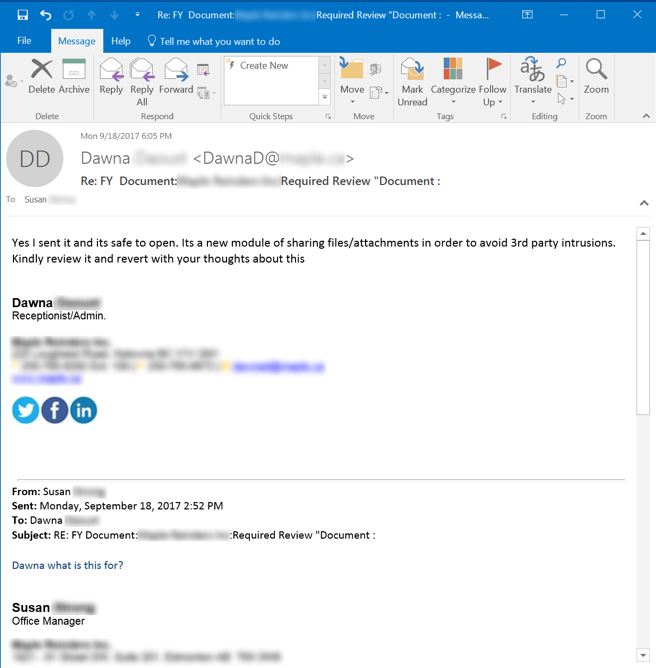

After answering Susan's question, the bad guy helpfully goes on to provide instructions for opening the alleged file.

Two things, however, mar his response. First, the provided explanation for the file doesn't make much sense (perhaps the bad guys were counting on the user being less than technically savvy and, thus, being accustomed to these kinds of nonsense explanations?). Second, this file, allegedly necessary to prevent "3rd party intrusions," is being distributed by a receptionist -- probably not the most reliable source for security fixes, be they from inside or outside the company. As with our previous example, the response appears to be boilerplate.

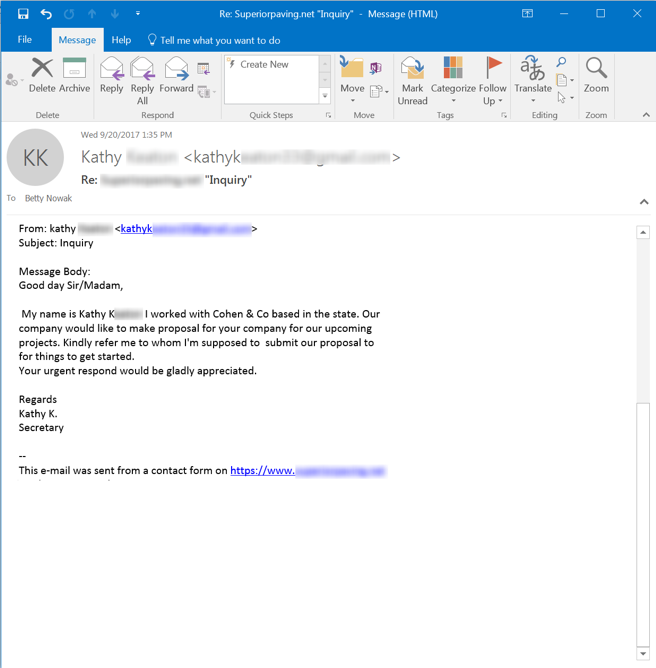

Our final example leads off with a referral request:

The employee in this situation, however, responds not with a question but with a perfunctory answer that points the bad guy in the "right" direction:

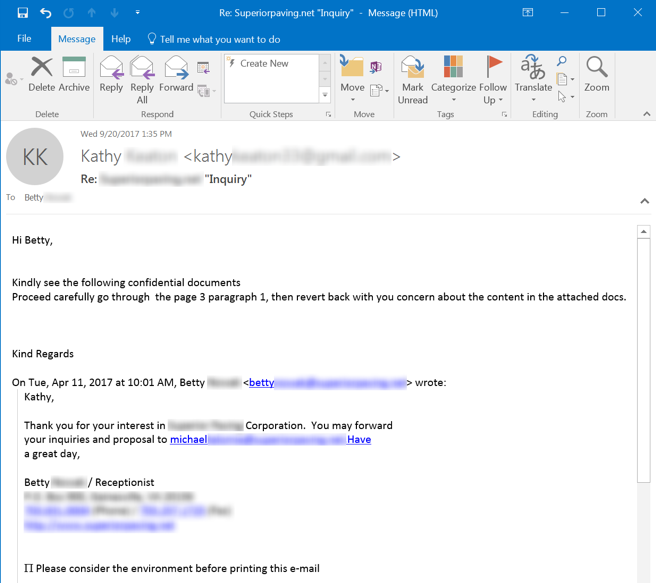

Amazingly, the malicious actor appears to ignore the golden information provided by Betty and plows on ahead with simple boilerplate. Still worse, the bad guy fails to include the malicious attachment referenced in that boilerplate.

If nothing else, the examples we've looked at here demonstrate that the malicious actors running these campaigns are not nearly as adept at rolling with the punches and providing credible responses to potential marks who reply to their initial phishing salvos. Boilerplate, bad English, and unresponsive explanations crippled these attempts at social engineering vulnerable employees.

Dancing in the Dark

We shouldn't be too quick to take comfort in the bad guy failures on display in the email exchanges documented above. The groups now supporting mass phishing campaigns with email exchanges are still learning and will undoubtedly get better at doing it and become more credible in the process.

As we noted at the outset of this piece, for all too many employees the experience of handling phishing attacks is a solitary experience. Sitting alone at their desks, your employees are making critical decisions concerning the security of your company's network and operations on a daily basis. And they're making those decisions alone, usually without much input or guidance from anyone else.

The bad guys are looking to change that by engaging more directly with your employees, providing them reassurances when they get nervous about opening malicious links and attachments, and holding their hand to walk them through the process of compromising their desktops as well as your company's network.

New-school Security Awareness Training is critical to enabling you and your IT staff to connect with those employees and help them make the right decisions so they aren't left dancing the dark with savvy criminals determined to exploit your employees' vulnerabilities and convert your organization into their own private cash machine.

Our new Phishing Reply Tracking allows you to track if a user replies to a simulated phishing email and can capture the information sent in the reply. You can also track links clicked by users as well as test and track if users are opening Office attachments and then enabling macros.

PS: Don't like to click on redirected buttons? Cut & Paste this link in your browser: