Over the past month or so customers using the Phish Alert Button (PAB) have been reporting a curious wave of what initially appeared to be run-of-the-mill tech support scam emails. As it turns out, the operation being run here on unsuspecting consumers is definitely not your usual tech support scam.

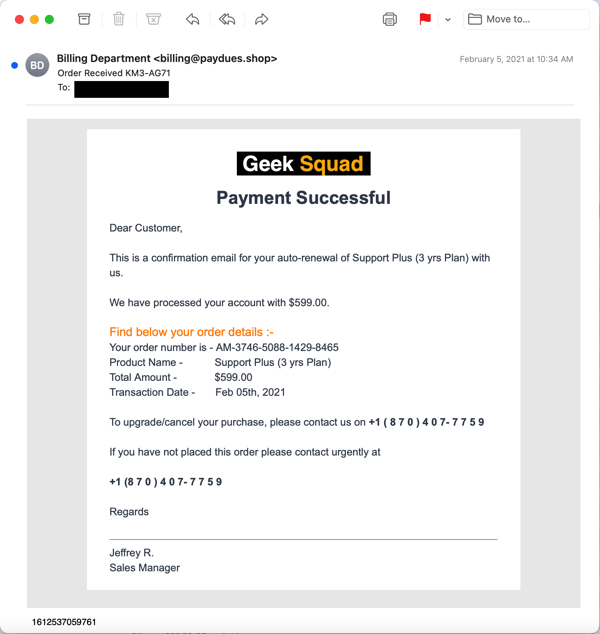

These scam emails announce that your subscription to some software product (usually a security product like Malwarebytes) or online service (like Geek Squad) has been automatically renewed at some outrageous price — usually in the neighborhood of $400-$600. The email provides a number to call if you want to cancel the subscription.

Over a number of weeks the volume of emails being reported kept growing, as did the variety of well-known brands and products being named and referenced in the emails.

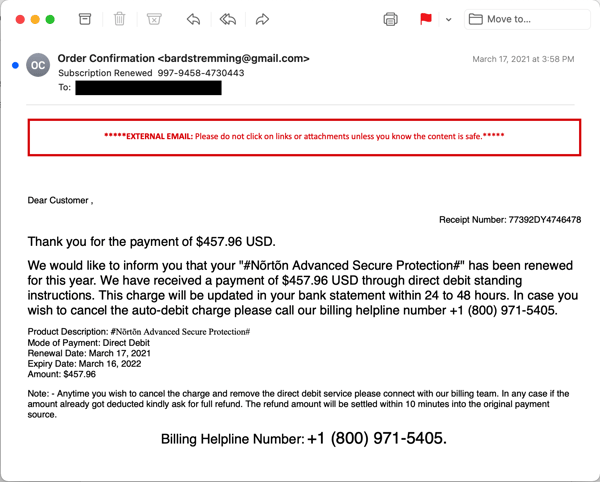

Curious, we decided to take the plunge and find out what was going on. The particular email we selected to use was a fairly typical example of the genre that pushed a subscription to a non-existent Norton product:

Now, your average tech support scam (which can be run through malicious emails, deceptive online advertising, or even cold calls direct to consumers' phones) typically has one goal -- namely, to get a credit card number out of the victim to pay for bogus online support services. Some variants of this basic scam will attempt to up-sell victims into purchasing additional products and services. Almost all of these scam operations manipulate victims by using remote control tools to connect to victims' PCs, demonstrate (non-existent) problems on their PCs, and then demand a credit card to fix those issues.

What we discovered when we finally crawled down that rabbit hole was rather surprising. In short: this is not your average tech support scam designed to extract a credit card from victims. Oh, no. The end game for these "subscription renewal" scams is much, much worse than we expected.

The scam being run through this recent wave of malicious emails turns out to be a rather elaborate affair. The whole process involved talking with two different individuals in two different Indian call centers and the installation of no less than three different remote control tools (along with Google Chrome).

Let's walk through what happened when we called the number in that fake Norton subscription email.

The First Call

When we called the number provided in the email, we expected that the tech answering would be well-prepared to handle the initial befuddlement and skepticism that could be expected among bewildered and concerned consumers facing an unexpected $500 subscription auto-renewal. And indeed that turned out to be the case.

The tech you connect with calmly listens to your questions and protests, then proceeds to tell you that the software was probably installed inadvertently while you were browsing the web. (After years and years of surreptitious adware installs online and mysterious toolbars and other programs unexpectedly showing up on consumer PCs, this might strike many users as credible.)

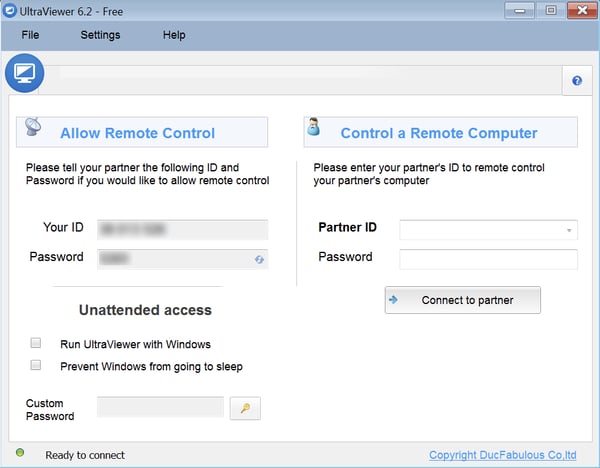

After you state that you never wanted the software and tell them you’re sure it’s not even installed on your PC, they insist that it is in fact on your system and offer to remove said software for you and refund the money. The initial tech who fields your call then instructs you to download a remote control tool (Ultraviewer in our case) and walks you through the process of allowing him to connect to your computer.

The tech then proceeds to outline what will be happening next. You are told to expect a second tech to be calling in a few minutes. Just in case that second tech doesn't call, the first tech provides you with a phone number you can call. After leaving the virtual PC in a state (mostly) ready for the second tech, the first tech disconnects from the call.

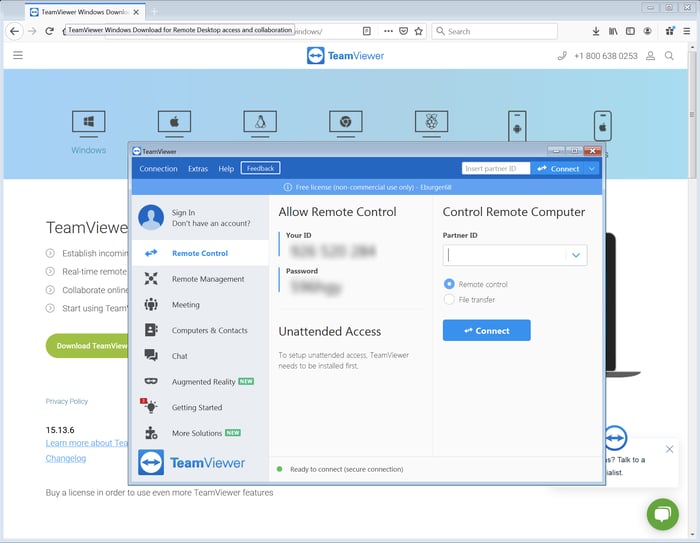

After disconnecting -- but before the second tech calls you -- the first tech downloads a second remote control tool (TeamViewer in our case), installs it on the PC, and leaves it open -- effectively handing the case and your PC over to the second tech.

The Second Call

After five or ten minutes, the second tech connects to your PC using Teamviewer. He then proceeds to download a third remote control tool (AnyDesk) and re-connects with that.

At that point the second tech calls you from what sounds like another call center (background noise on the second call in our case was noticeably louder than the first).

Now the fun part begins.

The second tech explains that they’re going to refund your money by making a direct bank transfer, claiming that is the only way they can do it. (No, they can't simply do a standard charge-back.)

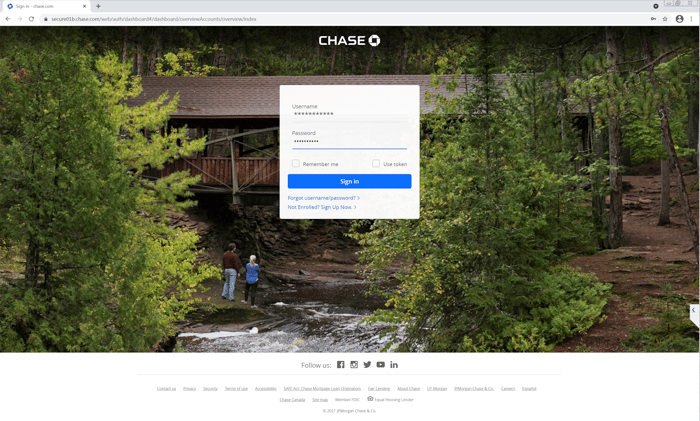

The tech then opens your browser to Chase Bank -- where the folks behind operation presumably have an account -- and prepares to log in with their credentials without actually completing the login process.

Whether the bad actors behind this scam actually have a Chase account remains an open question. As we note later in this piece, this visit to Chase bank site may all be for show. Still, at this point in the second call we were kicking ourselves for not having a key logger installed in our VMware session.

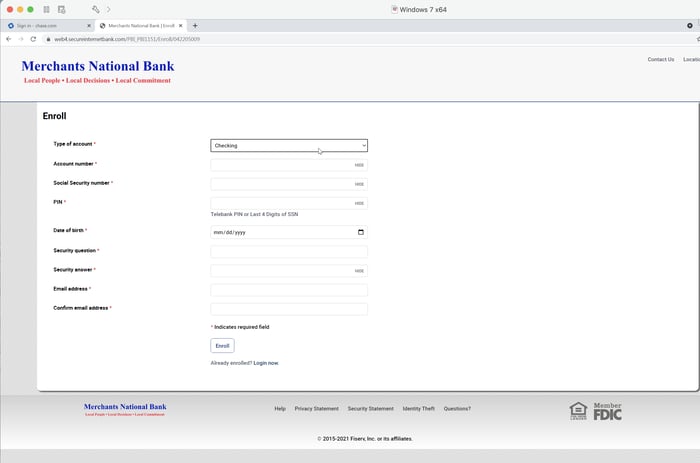

The second tech then asks you to log in your own bank account. We played dumb and said that we usually got paper statements from our bank, that we had never logged in to that bank’s web site, and that we didn’t even know the URL for it. (This answer had been set up by details we had earlier given both techs to casually reinforce the idea that we were not very tech savvy.)

The tech took this all in stride and helped us find the bank via Google (we identified a bank in another state that we happened to be be familiar with). He then searched around the bank’s site until he figured out how to create an online account at that bank.

At that point the whole process stalled because we told him we were at a friend’s house -- the same friend we earlier reported had been the one to set up our PC -- and didn’t have our bank account number handy. (Without money to burn in a bank account used solely for bait, we simply could not proceed but still wanted to preserve the ruse to the end.)

The tech put us on hold while he conferred with a manager. After resuming the call, he explained that he would call us back later. We told him we didn’t know when we’d be back home and that we would call him when we returned. He acknowledged, left a phone number, and told us he would wait for our call.

At that point the second call ended.

Notes & Observations

We are fairly confident that, had we continued with a working bank account, there would have been a money transfer — just not in our favor. This is undoubtedly the ultimate end game of this rather involved and lengthy scam: to obtain direct access to the victim's bank account and transfer money out of it. We do not know whether the amount transferred would be limited to the price quoted in the original email or some larger amount, perhaps taken after the victim's bank credentials had been stolen.

As noted earlier, we are not even sure that the fraudsters behind this operation even have a Chase account — that might all have been for show. Instead, they may be just counting on capturing the victim's bank credentials.

All in all, this was quite an elaborate ruse, taking well over 30 mins from start to finish and involving two techs, two separate phone calls, and three remote connections along with the installation of four different software programs (three remote control tools plus Google Chrome).

The payoff for the bad guys, however, is potentially huge.

The two techs who handled our case seemed very well prepared to navigate any obstacle they might encounter:

- The first tech took the time to reconnoiter the landscape, asking us what kind of computer we had, how old it was, and what we used it for. He even double-checked to see if it might be a work/business machine. Similarly, the second tech asked about our bank account -- whether it was checking or savings. (We told him it was a checking account with a savings account attached.)

- When we told the first tech that we were pretty sure the program (Norton) wasn’t on our PC, he patiently explained that we had probably inadvertently installed it while browsing the web, that it was probably hidden somewhere on the PC, and that he, a professional technician, would find and remove it for us.

- When the Firefox browser in our VMware session refused to connect because it was out of date, the second tech simply downloaded Chrome and installed it.

- When we told that same tech we didn’t know how to find our bank online, he led us right to the front door and was prepared to guide us through the task of setting up an online account.

Nothing phased these guys. Moreover, they were exceedingly polite and efficient the entire time. They also established their authority very early in the call and used it to drive the process from one step to the next. Given their performance, it's fair to assume that both techs have enjoyed plenty of experience working in call Indian call centers that regularly deal with American consumers.

One noteworthy touch was that both techs emphasized their concern for our privacy and security. Indeed, the second tech actually went a bit overboard in telling us how safe the entire process was, instructing us not to reveal any personal information over the phone with him, and stressing that the process we were following would protect our information. He returned to these themes repeatedly.

Despite the length and complexity of this operation, it gave every evidence of being well thought-out and thoroughly scripted. Moreover, the techs had clearly been well-trained and were completely prepared to handle every twist and turn in the process.

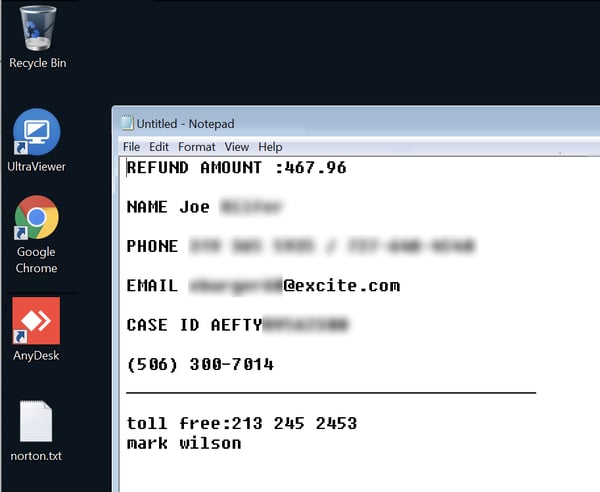

Example: to facilitate the call, the first tech opened Notepad and began adding information (Case ID and so forth). He then asked us to add some information ourselves (name, phone number, email, etc.). The second tech later used the info from that same file after he connected, later adding further information himself and saving it to the desktop.

That plain text file effectively functions as a record of the call/case that can be then used in further sessions with any other tech who happens to get involved.

One final note: some readers might be wondering why this operation required the use of three different remote control tools. We are not completely sure, but we're assuming that spreading this scam process across three tools and three different remote connections might make it more difficult for law enforcement authorities to investigate the scam and establish precisely what happened.

Conclusion

This "subscription renewal" scam is a worrisome evolution and escalation of the familiar tech support scams that have been around for years. Although clearly directed at home consumers, emails pushing this scam are now landing in corporate inboxes at email addresses that many of your employees might already be using for their own personal business, including online shopping, subscriptions, banking, and credit card statements.

Bad actors have the talent and the inclination to develop and execute amazingly elaborate scams like the one documented here. Your users' best hope for handling the malicious emails that kick off these kinds of scams -- as well as more standard phishing campaigns designed to leverage your employees' gullibility to penetrate your network -- is New-school Security Awareness Training.

Do your yourself, your organization, and your employees the favor of stepping them through the security awareness training they need and then testing their preparedness with simulated phishing emails.

Security Awareness Training is critical to enabling you and your IT staff to connect with users and help them make the right security decisions all of the time. This isn't one and done. Continuous training and simulated phishing are both needed to mobilize users as your last line of defense. Request your one-on-one demo of KnowBe4's security awareness training and simulated phishing platform and see how easy it can be!

Security Awareness Training is critical to enabling you and your IT staff to connect with users and help them make the right security decisions all of the time. This isn't one and done. Continuous training and simulated phishing are both needed to mobilize users as your last line of defense. Request your one-on-one demo of KnowBe4's security awareness training and simulated phishing platform and see how easy it can be!